Regorafenib, a multi‑kinase inhibitor, has limited efficacy in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) due to dose‑-dependent toxicity. The present study explored whether low‑dose Regorafenib combined with Nifuroxazide exerts enhanced anti‑tumor effects in HCC models. In vitro experiments with HepG2 cells showed the combination inhibited cell viability, proliferation and migration, induced apoptosis and reduced expression of key proteins, including phosphorylated signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3). In vivo, H22 tumor‑bearing mice treated with the combination exhibited suppressed tumor growth without systemic toxicity, along with changes in apoptotic proteins, enhanced tumor‑infiltrating immune cells and improved systemic immune responses. These findings indicated that the combination exerts enhanced suppression of HCC by inhibiting STAT3 and remodeling anti‑tumor immunity, providing preclinical evidence for a safe and effective strategy.

Product Citations: 272

In Oncology Reports on 1 April 2026 by Li, K., Chen, J., et al.

-

FC/FACS

-

Mus musculus (House mouse)

-

Cancer Research

-

Immunology and Microbiology

In Nature Communications on 14 February 2026 by Zhang, Z., Li, X., et al.

Discovering more targets is of great importance for developing alternative interventions for tumor therapy. The roles of transmembrane protein 175 (TMEM175) in neurodegeneration diseases have been reported, however its functions in tumor immune surveillance are not known. We show that TMEM175 conditional knockout in macrophages inhibits the tumor growth and metastasis through promoting the anti-tumor immunity in the tumor microenvironment (TME), including elevated M1-like polarization, reduced M2-like polarization, and facilitated recruitment and activation of T cells and nature killer cells (NKs). The anti-tumor immunity is abrogated by caspase-1 inhibitor VX-765, anti-IL-1β, and anti-IL-18. Tmem175-/- bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs) show enhanced tumor antigen cross-presentation that is further strengthened by IL-1β and IL-18. NLRP3 is robustly elicited in Tmem175-/- BMDMs by the tumor cell debris through lysosomal permeabilization and cathepsin B leakage. Finally, Tmem175-/- mice are more responsive to anti-PD-1. Our works implies TMEM175 to be a potential target for immunotherapy.

© 2026. The Author(s).

-

Mus musculus (House mouse)

-

Cancer Research

-

Cell Biology

-

Immunology and Microbiology

In Blood Vessels, Thrombosis & Hemostasis on 1 February 2026 by Parachalil Gopalan, B., Kamimura, S., et al.

Vaso-occlusive crises, thrombosis, inflammation, and immune dysregulation contribute to organ damage and poor outcomes in sickle cell disease (SCD). Because neutrophils and dysregulated extracellular trap formation (NETosis) contribute to sickle pathophysiology, and the spleen tyrosine kinase (Syk) signaling pathway is a key driver of NETosis, we investigated the effect of targeting Syk with fostamatinib (R788). Specifically, we studied the effect of a selective Syk inhibitor, R788, on hematologic and biochemical parameters, NETosis, platelet P-selectin expression, and platelet-neutrophil aggregate formation in Townes sickle mice at baseline and after exposure to pathophysiological stressors (tumor necrosis factor α [TNF-α] and hypoxia-reoxygenation). Our results showed that at baseline R788 impaired hematopoiesis, and worsened anemia and neutropenia in sickle mice. Additionally, R788 at nontoxic doses had little, if any, effect on NETosis and platelet activation induced by TNF-α or hypoxia-reoxygenation. Severe anemia and neutropenia induced by R788 in the sickle mouse model suggests that concomitant use of Syk inhibitors with hydroxyurea in patients with SCD should be approached cautiously. Further research is required to clarify the benefits and risks of selective Syk inhibition in SCD and other hemolytic conditions exhibiting stress hematopoiesis.

-

Mus musculus (House mouse)

Preprint on Research Square on 26 January 2026 by García-Sancha, N., Corchado-Cobos, R., et al.

Abstract Breast cancer that arises in the postpartum period often carries a poor prognosis. The increasing trend of later-life pregnancies further exacerbates this risk. We urgently need chemoprevention strategies that reduce risk for postpartum period tumors, especially for more-aggressive ER-negative tumors and for those that arise in women with a genetic susceptibility. Here, we report that a single post-lactation dose of cabergoline, a dopaminergic agonist that blocks prolactin secretion, delays the onset and reduces the incidence of mammary cancer that arises postpartum in K14-Cre; Brca1 F/F , Trp53 F/F mice. In these mice, cabergoline treatment remodels the postpartum mammary gland by potentiating involution, reducing ductal area and proliferation, and reversing T cell exhaustion, potentially through modulation of ion channel expression. Notably, independent retrospective studies in two large cohorts of European women demonstrated a markedly lower incidence of postpartum breast cancer in those treated with cabergoline compared to a control group, with a meta-analysis indicating an approximate 69% reduction in risk. Our work underscores the importance of targeting post-lactational involution as a strategy for the prevention of postpartum breast cancer and identifies cabergoline as a novel, low-risk chemoprevention strategy during the vulnerable postpartum window by promoting physiological remodeling and mitigating immune dysfunction.

-

Cancer Research

Preprint on Research Square on 19 January 2026 by Planas, A., Pedragosa, J., et al.

Abstract Central nervous system border-associated macrophages (BAMs) reside at the interfaces of the cerebrospinal fluid, the brain parenchyma, and the vasculature, positioning them as key sensors of cerebrovascular injury. We examined the response of BAMs to ischemic stroke using mice engineered to report combined Cx3cr1 and Lyve1 expression. Stroke induced proliferation of embryonically derived BAMs and promoted their acquisition of a pro-inflammatory state along with MHC-I-mediated enhanced antigen presentation capabilities. MHC-I upregulation was driven by the delayed activation of a type-I interferon (IFN-I) program. Although CD8+ T cells were largely bystander-activated after stroke and infiltrated the brain in an antigen-independent manner, BAMs interacted with infiltrating CD8+ T cells in both mouse and human brains. Overall, the study shows that stroke reprograms BAMs into an IFN-I–driven, antigen presenting state that can enhance CD8+ T cell-mediated immune surveillance in the brain.

-

Cardiovascular biology

-

Immunology and Microbiology

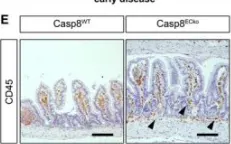

In Nat Commun on 6 August 2022 by Jung, S. H., Hwang, B. H., et al.

Fig.1.A

-

FC/FACS

-

Collected and cropped from Nature Communications by CiteAb, provided under a CC-BY license

Image 1 of 4

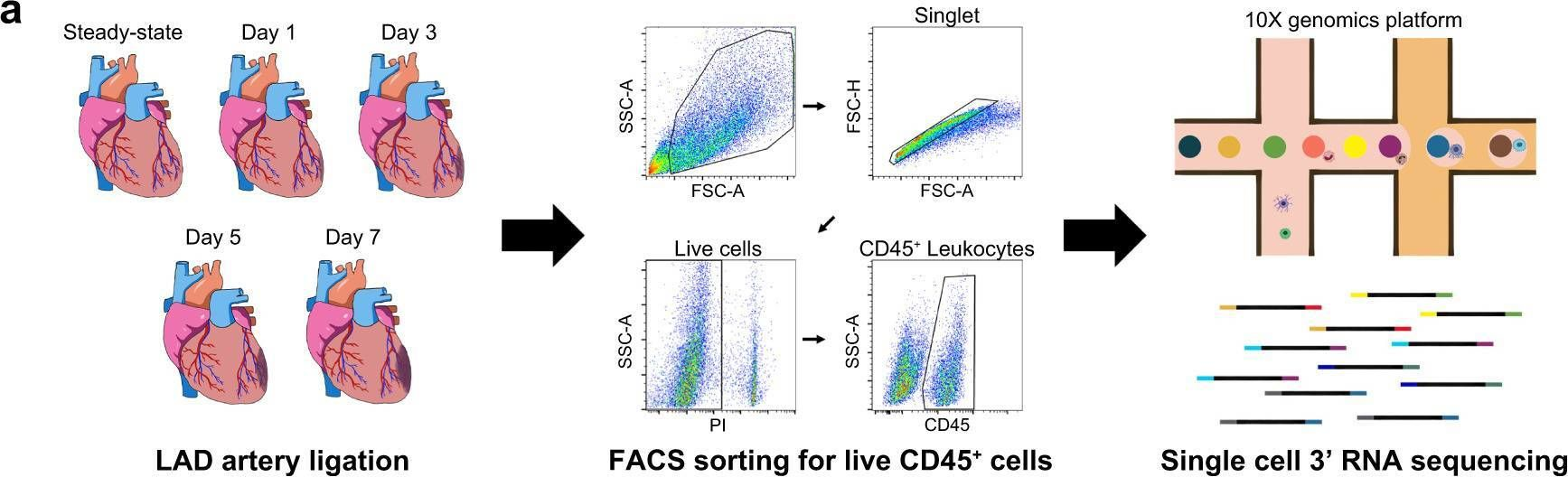

In EMBO Mol Med on 8 June 2022 by Tisch, N., Mogler, C., et al.

Fig.2.E

-

IHC

-

Mus musculus (House mouse)

Collected and cropped from EMBO Molecular Medicine by CiteAb, provided under a CC-BY license

Image 1 of 4

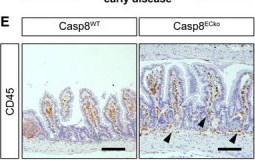

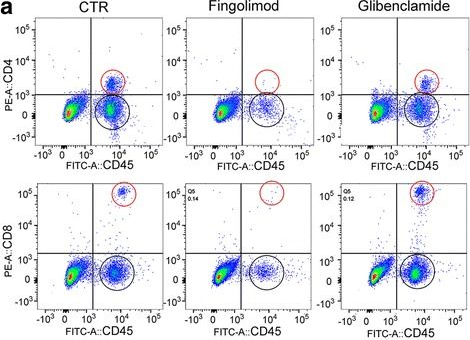

In Sci Rep on 5 June 2019 by Salas-Pérdomo, A., Miro-Mur, F., et al.

Fig.2.D

-

FC/FACS

-

Mus musculus (House mouse)

Collected and cropped from Scientific Reports by CiteAb, provided under a CC-BY license

Image 1 of 4

In J Neuroinflammation on 2 September 2017 by Gerzanich, V., Makar, T. K., et al.

Fig.5.A

-

FC/FACS

-

Mus musculus (House mouse)

Collected and cropped from Journal of Neuroinflammation by CiteAb, provided under a CC-BY license

Image 1 of 4